Andrew Lewis Aycock

James Ralph Scales, Wake Forest President, at April 12th 1978 Funeral for ANDREW LEWIS AYCOCK

The burden of this occasion is to remember Andrew Lewis Aycock and to reaffirm the values that he stood for. I am especially apprehensive that what we say may not be worthy of the man. “Words, ” says T. S. Eliot, “slip, slither, decay with imprecision.” This brief farewell salute may not be chiseled in stone, but it must be precise, else I risk the rebuke of the well remembered voice, “Dr. Scale s, just what do you mean by that?”

He was a perfectionist who expected his collaborators and his students to work hard, and he worked even harder. He impressed me, as he must have impressed all others who knew him, as one of those rare beings endowed with an abundance of ability as well as the scholar’s discipline. In a world increasingly specialized, he was a gifted generalist. He understood his business, and he would have been amazing had he devoted himself entirely to the teaching of English.

But he did more. Some uninformed people, relying only on the formal documents, tell us that we have had an art department for only a decade. They are mistaken. A. Lewis Aycock has been an art department for almost half a century, having well established his qualification in English, he entered the great history-of-art program at Harvard in the summer of 1933, and the date tells us much. In the midst of the depression, the young teacher spent his slender resources pursuing a subject that needed to be taught to young men in a rural North Carolina college.

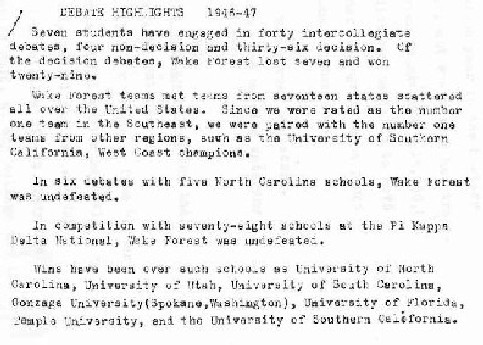

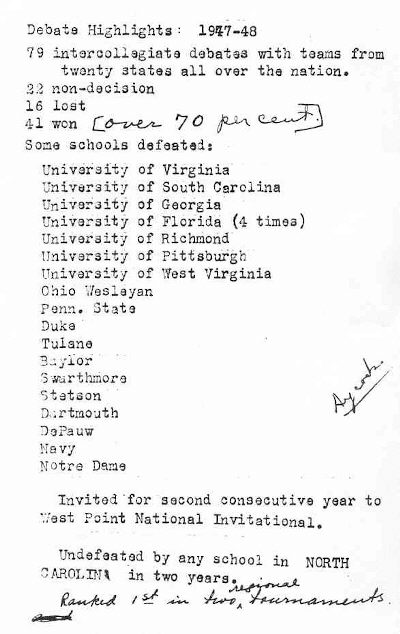

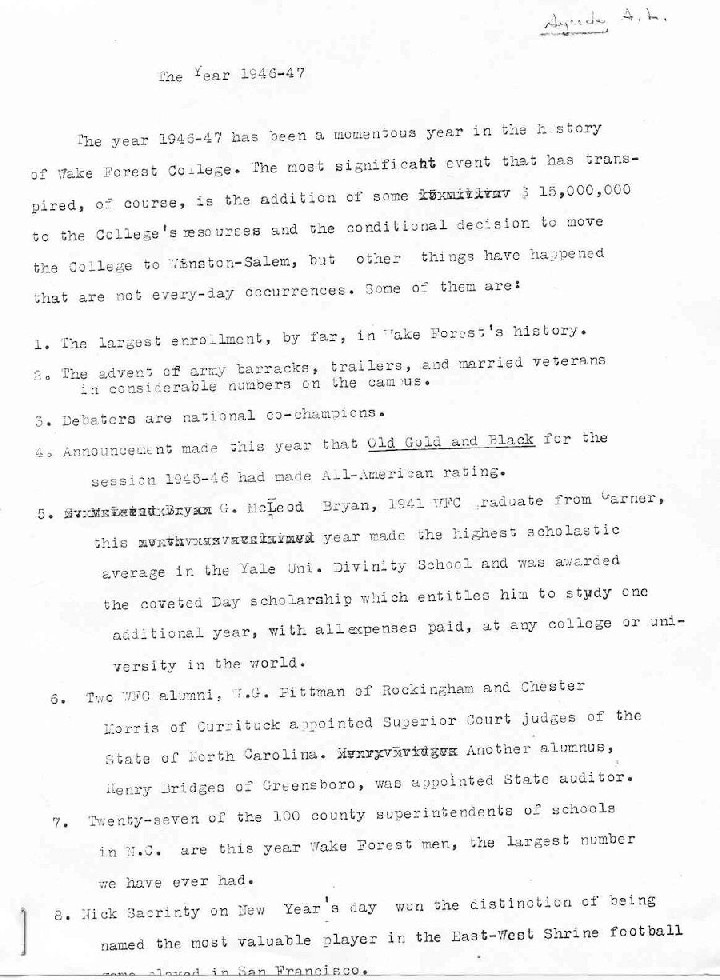

The printed catalog has announced a Department of Speech for only a generation or so, and that too fails to reflect the fact that Lewis Aycock was the coach of a national championship debating team long before formal studies in forensics existed.

He used his considerable talents, influence and spirit to strengthen every part of the enterprise he loved. His were great gifts – – a fine education that commanded respect, and a desire to impart learning to young people. Friends who knew of his labors did not embarrass him by flattery. Such would have been sternly suppressed. Even so, that stately dignity was betrayed ever so often, and unexpectedly, by a mischievous glint in the eye, a touch of literary humor. Above all, he blended his passion for beauty and a finely tempered integrity to organize the work of the College, so that he made life worth living for himself and others. He was not a do-gooder, but a doer of good. Whenever he promised to help he gave it, with energy and intelligence.

In my years of association with Professor Aycock, I came to rely on his judgment in many matters, especially in the preservation of our artistic heritage. He would not have approved the neologism, but to me he exemplified the unflappable. He could be eloquent, vigorous, even emphatic, in setting forth his views of education and the meaning of the university, and in doing so, he called forth a creative response in all of us. Surely his was the ideal of Matthew Arnold, to see life steady and to see it whole. For many decades he gave personal leadership to the conservation of the Simmons Art Collection, which filled the small gallery on the old campus and has been distributed on this. He had the grace of gratitude and, while recognizing the Simmons Collection as only a nucleus, he encouraged what has become a well nigh universal interest in the collection of our fine arts. I am glad that he could see the completion of the new Fine Arts Center, which includes an envied collection of 90,000 slides of the world’s great art, much of it brought together by Lewis Aycock.

He was honored on this campus for his taste, fore sight, and discrimination. For the gentle urging of his mind and the constant prodding of those in authority, the arts flourish at Wake Forest. He did much to restore our pride and pleasure in the elegant and beautiful.

Faculty Resolution Upon the Passing of A. Lewis Aycock

The death on .April 10, 1978, of Andrew Lewis Aycock, Professor Emeritus of English, brought to an end a long admirable life, a large part of which was spent in devoted service of Wake Forest University.

Mr. Aycock joined the Wake Forest faculty in 1920 as an instructor in the department of English. He brought to the teaching profession academic credentials of a high order. He graduated from Wake Forest College in 1926 – with the B. A. degree cum laude. He received the M. A. degree in 1928 from Tulane University, where he was Robert Sharpe Teaching fellow in 1927-28. He spent the year 1932.-33 doing additional graduate study in English at Johns Hopkins University. Mr. Aycock’s area of special interest was English literature of the 16th and 17th centuries; and for years he taught a course in John Milton , the great 17th-century poet. From the start of his career Mr. Aycock was also involved in lower-division work; and over the years his emphasis in teaching shifted from literature to composition. For many years he was director of freshman English and regularly taught classes in freshman composition. He also taught for many years a course for English majors in the teaching of English in high school. Further evidence of his interest in such work as his long and active membership in the North Carolina English Teachers Association and in the National Council of Teachers of English. In the light of the reputation he achieved in other fields, it is important to note that Mr. Aycock was always regarded by his colleagues, especially those who served with him in the English department, as, first and foremost, a skillful and notably successful teacher of English.

He was, however, active in other areas, displaying from the outset of his career the versatility that was one of his distinguishing characteristics. Within a year of joining the faculty he established his connection with art, a collection which contributed for more than four decades, to the cultural enrichment of the university. In the summers of 1929 and 1930 he studied in the history-of-art program at Harvard university, under a Grant from the Carnegie Corporation; and in 1930-31 began offering in the English department a course in ancient art. He later added two more courses, Medieval and modern , art and American Art. He continued his training in the field long after he had proven himself as a teacher. During much of the summer of 1949 he studied art at Columbia University; in the summer of 1951 he was again at Harvard, registering for three courses and doing special work in American art; and, a student to the last, he spent a good portion of the summer of 1966 in the Study Abroad Visual Arts Program of Temple University. Besides teaching art, he was from 1941 onward Curator of the Wake Forest College Museum of Art. He gave personal leadership to the conservation of the Simmons Art Collection on the old campus and to its safe removal to Winston-Salem. Almost single-handedly he maintained and greatly expanded the university’s collection of art slides, now one of the best collections in the Southeast, with more than 90,000 slides. When an art department was established at Wake Forest in 1968, Mr. Aycock became a member of its faculty. The slide library in the Fine Arts Center is named for him in honor of his many years of fruitful service to art.

In 1941, in response to the needs of the time and his own high sense of duty, Mr. Aycock took on responsibilities in yet another area. From 1941 through 1948 he served as Director of Forensics at the college. In one of these years the debating team coached by him went undefeated through the national tournament.

Mr. Aycock’s versatility led him briefly into administrative work. When an Office of Admissions was set up in July, 1957, he became its first director. He served as Director for two years, before returning to full-time teaching in 1959.

Mr. Aycock’s retired in 1971, after 43 years on the faculty, marked a diminishment not a cessation of active service to the university. Until the onset of his fatal illness he continued to work as curator of the art slides collection. He also worked extensively in building the collection of oral history of the university.

Throughout this long career of varied service Mr. Aycock was consistently held in highest respect by all members of the academic community. Generations of students found him to be an exceptionally able teacher: always in command of his subject, always thoroughly prepared for his classes, always scrupulously fair in his treatment of students, always obviously dedicated to their best interests, and always challenging them to get everything they could from their education. Generations of his colleagues shared this judgment of him as a teacher; and found added cause for admiration in his work outside the classroom. Toiling with him on committees of the college, they came to appreciate his readiness to do more than his share of the drudge that Committee work often involves; his penetrating intelligence and sense of the practical that enabled him to go to the heart of problems; his spirit of cooperative good-will that sought to bring harmony out of discord; and his courage, that could not be intimidated when he took his stand on matters he thought crucial to the well-being of Wake Forest and of liberal education. Students and colleagues alike saw in him the truth of Emerson’s observation about the true scholar: “Character is higher than intellect. They recognized that all his professional knowledge and skill were at the service of a nature impressive in its integrity, its devotion to high moral principle, and its complete freedom from anger, pride, envy, and duplicity. It was Mr. Aycock’ s happy fortune to be a living exemplum of the values Wake Forest University holds most dear. In his death Wake Forest University and liberal education have suffered a heavy loss.

I move that this resolution be adopted by the faculty; that copies of it be sent to Mrs. Aycock and to the Aycock’s’ two daughters, Delia and Jane; and that the faculty stand in a moment of silent tribute to Lewis Aycock.

Alonzo W. Kenion, Chairman

James Ralph Scales

Ediwin G. Wilson